Noortje Marres, (Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies, University of Warwick)

A short report of a guided walk organised as part of the CIM project Sampling Sounds of Coventry’s Future. The guided walk by Sarah Farmer took place on Sunday October 17, 2021, and was organised as part of Sampling Sounds of Coventry’s Future, a series of events created by the Centre for Interdisciplinary Methodologies and the Warwick Institute of Engagement, University of Warwick, for Coventry City of Culture.

Last Sunday the musician Sarah Farmer took us for a walk along Coventry’s Music Mile.

She had brought along several speaker-balls which she handed out to us, quite casually, and, after a quick explanation, they pretty much turned themselves on, waking us up with strings rumbling and reassuring blue light.

We were pulled along by this sound emanating from the little speakers, sound that I have a weakness for, slow strokes along violin strings reveberating, as we walked from FarGo Village, into Gosford Park, and up along Walsgrave Road, us following the sound, and Sarah Farmer, who, like a piped piper, walked in front, except she seemed quite unconcerned with us following her.

She, or rather the instruments she has brought along, let us hear different sounds of Coventry, as if picking up signals from the environment around us – Dub, Jamaican steel drums, folk violin play. As we walked, different melodies would emerge from the violin strings reveberating from our little speakers, then fade away, into the background.

I know Dub and steel drums from different places, but these were unfamiliar sounds, almost all unknown to me, a visitor of Coventry, still, after coming here regularly for six years now.

The different sounds had a searching quality, as if they too, were looking still, to figure out how to inhabit this city, which for several of us on this walk, though certainly not all, remains quite unfamiliar. Some of us just arrived in Coventry, literally from the other side of the world.

“Somewhere there.” Sarah, gesturing vaguely, across that wall, is Planet Studios, world famous, for the Asian artists who recorded there, Bhangra music, Asian fusion, and continue to do so, the studios are still going strong.

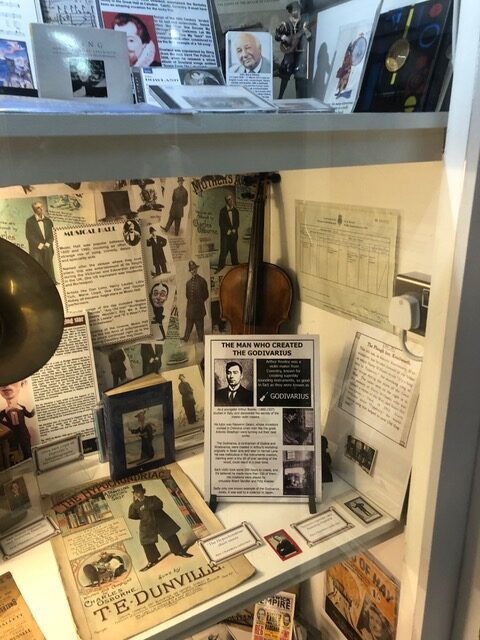

She points in the direction of the bandstand in Spencer Park, on the other side of the city centre – a park I know, a place to play, to hang out – and tells us the Godivarius may well have been played there, along side T.E. Dunville, who was described by Charlie Chaplin as “an excellent funny man.”

We hear other strings, played by a British Folk legend, unknown to me, who stuck the speaker part of a phone to his violin. Several of us nod, they know him well. He lived in Coventry for some years.

Sarah tells us about a remarkable habit of string instruments in general and violins in particular: when no-one one plays them and they are just sitting in their box, their strings may start resonating with sounds they pick up in their surroundings, when they recognise the pitch of their own strings – G, D, A, E. The technical term, I learn later, for this way of a violin being played by its surroundings is ‘sympathetic resonance.’

We walk into Ball Hill. I believe it is here my partner’s mother lived for several years, right after the Second World War, when she, age 10, arrived as a refugee from Lithuania. I only recognise it now, as we walk up the hill, past the Library, closed and with much reduced opening hours announced on the door, a sombre reminder of a cultural life not quite happening, so much reduced now.

And so we walk, in stops and starts, getting closer to the Coventry Music Museum, and the instrument we are drawn towards, the Godivarius, on display there. This mythical instrument, so it turns out, is also quite real, and can be found in a vitrine on the second floor of the museum, half hidden behind the label describing the man who created the instrument.

The Godivarius, a 19th Century violin, was crafted by a Coventry-based master, Arthur Rowley, who had trained in Italy with a tutor from Cremona (Italy) where Stradivarius is from.

Next time, when I hear “manufacturing” and “Coventry” in one sentence, I will think “violin.”

We arrive in 2 Tone village, where the Coventry Music museum is based, and I have a brief encounter with a man with a twinkle in his eye – he asks, how was it? I registered for this walk, he says, but then I realized it was people who are not from here who are behind it.

There it is, a line drawn between those who are and those who are not, from Coventry, or as Elena Ferrante has it, between those who stayed and those who left. He has a point, in questioning whether we know what we are doing: the Web page announcing the guided walk suggested a very long duration for this relatively short walk.

Onwards, into the museum, where we find Delia Derbyshire, a lifesize cut-out figure, the sound artist and composer of electronic music, also from here, Coventry, and who worked in the illustruous BBC Radiophonic workshop.

She could become that person, at a time when electronic music was not yet the world of famous (mostly) men that it is now, well done. I think of Data Knitting, the book by Sadie Plant about the women coders who programmed computers before coding became associated with the male heroism that marks it now. She worked at the University of Warwick, did she write this in Coventry?

We walk back, past the pub where, appararently, the Specials played Ghost Town, to which I danced as a 16 year old, in a different country, a different city (Hilversum), loving the song without knowing the city it mourns, calls out and celebrates all at once.

23 October 2021.

Photos by Nirmal Puwar (Sociology, Goldsmiths).